思维导图作者:

Summer,女,QE在职,梦想能仗走天涯 翻译/音乐/健康

02 第十四期写作精品课

写作课共5位老师

3位剑桥硕士3位博士在读(剑桥,杜伦,港理工)

5位雅思8分(其中两位写作8分,3位写作7.5分)

雅思、学术英语写作,不知如何下笔如有神?

写作精品课带你谋篇布局直播课+批改作文,

带你预习-精读-写作-答疑从输入到输出写出高质量英语作文03 新手必读

现在翻译组成员由牛津,耶鲁,LSE ,纽卡斯尔,曼大,爱大,圣三一,NUS,墨大,北大,北外,北二外,北语,外交,交大,人大,上外,浙大等70多名因为情怀兴趣爱好集合到一起的译者组成,组内现在有catti一笔20+,博士8人,如果大家有兴趣且符合条件请加入我们,可以参看帖子 我们招人啦!

五大翻译组成员介绍:(http://navo.top/7zeYZn)

1.关于阅读经济学人(如何阅读经济学人?)

2.TE||如何快速入门一个陌生知识领域(超链,点击进入)

在看越多,留言越多,证明大家对翻译组的认可,因为我们不收大家任何费用,但是简单的点击一下在看,却能给翻译组成员带来无尽的动力,有了动力才能更好的为大家提供更好的翻译作品,也就能够找到更好的人,这是一个正向的循环。

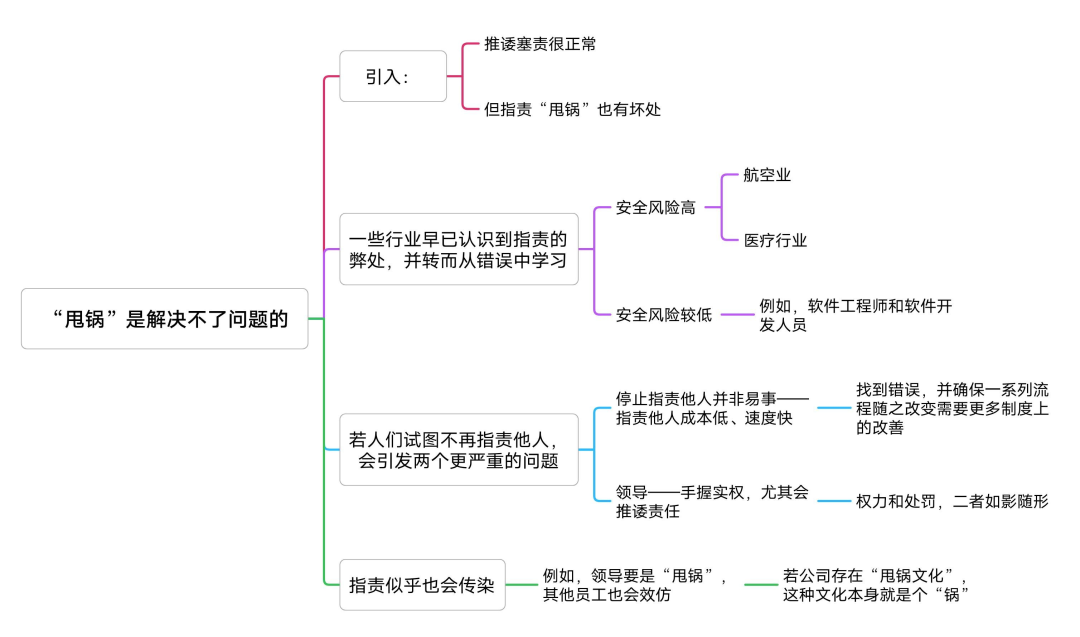

Why pointing fingers is unhelpful

“甩锅”是解决不了问题的

Why pointing fingers is unhelpfulAnd why bosses do it more than anyoneCasting blameis natural: it is tempting to fault someone else for a snafu rather than taking responsibility yourself. But blame is also corrosive. Pointing fingers saps team cohesion. It makes it less likely that people will own up to mistakes, and thus less likely that organisations can learn from them. Research published in 2015 suggests that a Shaggy culture (“It wasn’t me”) shows up in share prices. Firms whose managers pointed to external factors to explain their failings underperformed companies that blamed themselves.推诿塞责是正常的做法。面对事与愿违的情况,人们喜欢拉别人垫背,而不是自己承担责任。但指责也有坏处。互相指责会削弱团队凝聚力,让人越发不会承认自己犯下的错误,团队也因此更可能错失吸取教训的机会。2015年研究显示,可以通过公司股价看出该公司是否有“甩锅文化”(“不是我的锅”)。一些公司经理将失败归咎于外部因素,而这些公司的股价低于那些自省的公司。1. snafu n. a situation in which nothing happens as planned2. own up to sth.: To admit something, to confess.3. “Shaggy Culture” is a reference from a research published in 2015 which means someone does not take ownership of their actions and blames anyone else.4. 扩充:“推卸责任”可以怎么说?shirk/renege on one's responsibility/pass the buck/buck-passingSome industries have long recognised the drawbacks of fault-finding. The proud record of aviation in reducing accidents partly reflects no-blame processes for investigating crashes and close calls. The National Transportation Safety Board, which investigates accidents in America, is explicit that its role is not to assign blame or liability but to find out what went wrong and to issue recommendations to avoid a repeat.一些行业早已认识到推诿指责的弊处。在降低事故发生概率上,航空业有着引以为豪的记录,这在一定程度上反映出航空业在调查空难与紧急事故时的无责流程。美国国家运输安全委员会(NTSB)负责调查美国境内的事故,它明确表示自己的任务并非找到过错方或追究责任,而是发现事故原因,并提出改进建议措施,以防事故再度发生。1. no-blame processes: In the no-blame approach, all mistakes are treated as opportunities to learn, connect with others and gain insights at various levels2. NTSB的使命:调查事故,确定事故发生时的条件和环境,确定可能的事故原因,提出预防同类事故的建议,为美国各州的事故调查提供帮助。There are similar lessons fromhealth care. When things go wrong in medical settings, the systems by which patients are compensated vary between countries. Some, like Britain, depend on a process of litigation in which fault must be found. Others, like Sweden, do not require blame to be allocated and compensate patients if the harm suffered is deemed “avoidable”. A report published by a British parliamentary committee last year strongly recommended moving away from a system based on proving clinical negligence: “It is grossly expensive, adversarial and promotes individual blame instead of collective learning.”医疗行业也提供了类似的教训。出现医疗事故时,各国对病患的赔偿制度不尽相同。像英国等国,它们的赔偿取决于必然找出过错方的诉讼程序。而在瑞典等国,如果病人所遭受的伤害被认定是“可避免的”,则不要求责任认定与患者赔偿。去年,英国议会委员会发布的一项报告强烈建议弃用基于临床医疗过失证明的体系,其表示:“这么做成本巨大,扩散敌对氛围,使个体间相互指责,而不是共同汲取经验教训。”The incentives to learn from errors are particularly strong in aviation and health care, where safety is paramount and lives are at risk. But they also exist when the stakes are lower. That is why software engineers and developers routinely conduct “blameless postmortems” to investigate, say, what went wrong if a website crashes or a server goes down.航空业及医疗行业的人都很大动力从错误中学习,因为这两个领域安全至上,乘客和病人的生命都可能遭受危险。但就算某些行业风险较低,人们也有动力从错误中学习。因此,出现网站崩溃或服务器瘫痪时,软件工程师和软件开发人员往往会进行“无责善后”调查,针对“事故”原因一探究竟。There is an obvious worry about embracing blamelessness. What if the wretched website keeps crashing and the same person is at fault? Sometimes, after all, blame is deserved. The idea of the “just culture”, a framework developed in the 1990s by James Reason, a psychologist, addresses the concern that the incompetent and the malevolent will be let off the hook. The line that Britain’s aviation regulator draws between honest errors and the other sort is a good starting-point. It promises a culture in which people “are not punished for actions, omissions or decisions taken by them that are commensurate with their experience and training”. That narrows room for blame but does not remove it entirely.对于欣然接受“无责善后”的做法,人们明显还心存担忧。如果一直都由同一个人导致网站不停崩溃,该如何是好?毕竟有时,让人担责是必要的。心理学家詹姆斯·里森(James Reason)在20世纪90年代提出了“正义文化”这一构想。以解决对于能力欠缺者和心怀恶意者无需担责的担忧。英国航空监管机构也已在“无心之过”和“有意犯错”之间划定界限,这一举措无疑是个良好开端。它承诺创造一种文化环境:只要人们“做出的行动、产生的疏忽、做出的决定与其经验及所受训练相称”,他们便“不会受到惩罚”。这降低了推诿指责发生的可能性,但并没有完全消除该现象。There are two bigger problems with trying to move away from the tendency to blame. The first is that it requires a lot of effort. Blame is cheap and fast: “It was Nigel” takes one second to say and has the ring of truth. Documenting mistakes and making sure processes change as a result require much more structure. Blameless postmortems have long been part of the culture atGoogle, for instance, which has templates, reviews and discussion groups for them.若人们试图不再指责他人,会引发两个更严重的问题。其一,要停止指责他人并非易事,毕竟指责他人成本低,速度快。说一句“都怪奈杰尔”只需一秒,而似乎言之凿凿。找到错误,并确保一系列流程随之改变则需要更多制度上的改善。例如“无责善后”一直以来都是谷歌文化的组成部分,它有对应的善后模板、审查过程和讨论组。The second problem is the boss. People with power are particularly prone to point fingers. A recent paper by academics at the University of California, San Diego, and Nanyang Technological University in Singapore found that people who are in positions of authority are more likely to assume that others have choices and to blame them for failures.第二个问题在于领导。手握实权的人尤其会推诿责任。加州大学圣地亚哥分校和新加坡南洋理工大学的学者们近期发表的一篇论文指出,身居要职的人更容易认为他人本可以做出更好选择,也更有可能将失败归咎于他人。In one experiment, for example, people were randomly assigned the roles of supervisor and worker, and shown a transcript of an audio recording that contained errors; they were also shown an apology from the transcriber, saying that an unstable internet connection had meant they could not complete the task properly. The person in the supervisor role was much more likely to agree that the transcriber was to blame for the errors and to want to withhold payment. Power and punitiveness went together.比如,在一次实验中,将监管人员和工作人员的角色随机分配给实验对象,然后给他们一份有误的音频誊抄文本和誊写员的一封道歉信,信中称因网络连接不稳定导致他们无法顺利完成任务。拿到监管人员角色的实验对象更可能认为应将失误归咎于誊写员,也不想给他们报酬。权力和处罚,二者如影随形。Blame also seems to be contagious. In a paper from 2009, researchers asked volunteers to read news articles about a political failure and then to write about a failure of their own. Participants who read that the politician blamed special interests for the screw-up were more likely to pin their own failures on others; those who read that the politician accepted responsibility were more likely to shoulder the blame for their shortfall. Bosses are the most visible people in a firm; when they point fingers, others will, too. If your company has a blame culture, the fault lies there.指责似乎也会传染。在2009年发表的一篇论文中,研究人员让志愿受试者在阅读有关政坛失利的新闻后,写下自己的一次失败经历。那些读到“政客把事情搞砸归咎于特殊利益集团”的受试者,更有可能将自己的失败归咎于他人;而那些读到“政客愿意担负责任”的受试者,则更倾向为自己的不足买单。领导是公司里最受瞩目的人;领导要是“甩锅”,其他员工也会效仿。如果你所在的公司存在“甩锅文化”,这种文化本身就是个“锅”。Octavia,键盘手和古风爵士,逃离舒适圈,有只英短叫八爷